By Jacob Prater

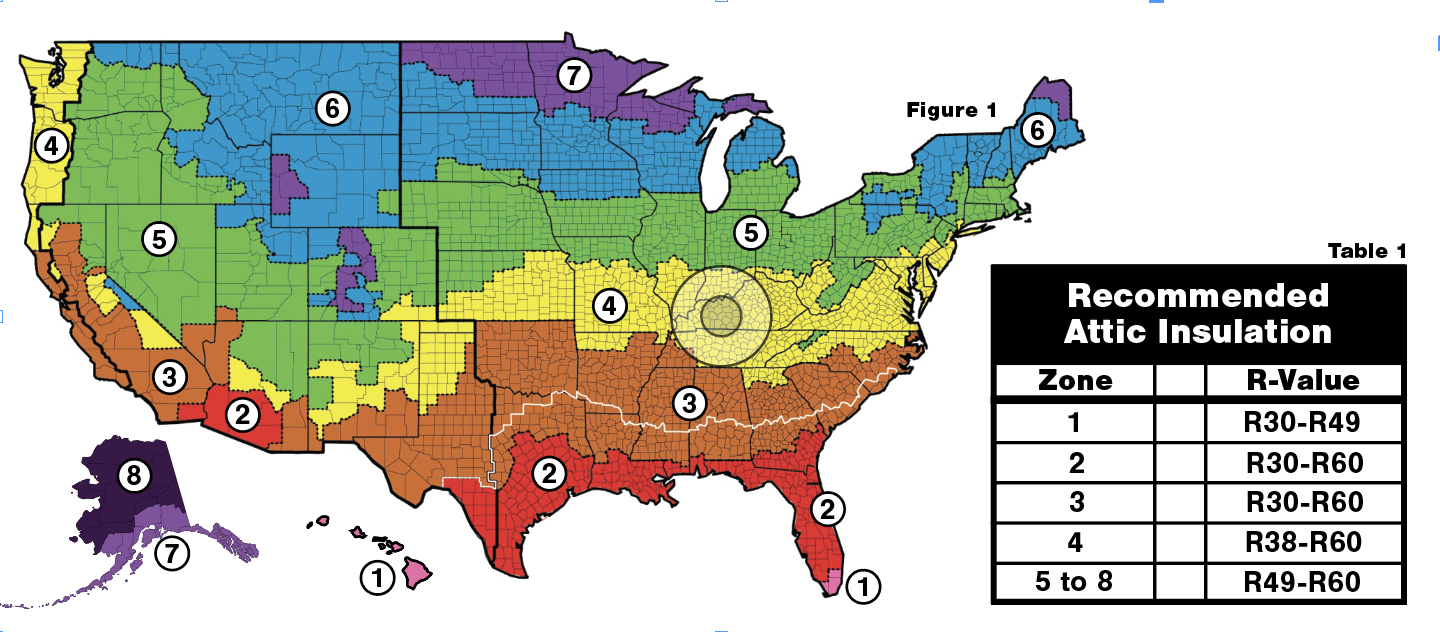

Many a mother has said to her child, “Put on a hat so that you don’t catch cold.” The analogy to a house or other building and roof or attic insulation is a good one here. The majority of heat loss in a house is upward through the ceilings, attics, and roofs similar to our heat loss through our heads. This heat loss through roofs and attics is on account of the fact that warmer air is less dense and has a tendency to rise. To combat this heat loss some pretty significant insulation is needed in an attic or roof. How much is needed — or rather how much is recommended — varies between climatic zones. A quick look at the Energy Star website can give you an idea of what is recommended for your locale (See Figure 1, Table 1).

R-value

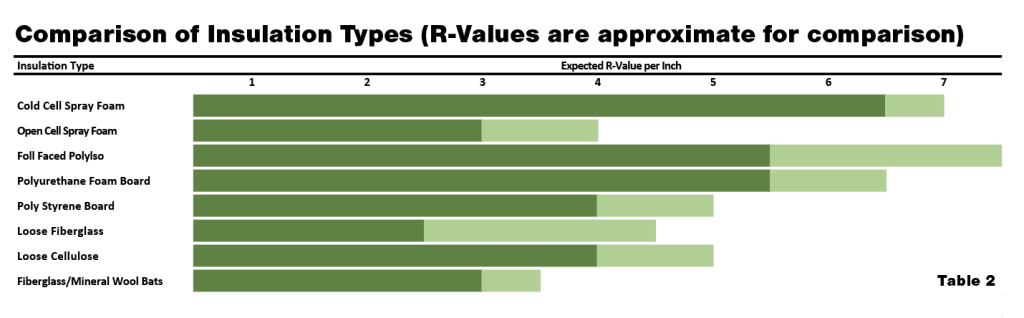

After this you have choices on how to achieve this R-value metric (Table 2). Certainly going a bit further with a higher R-value for a roof or attic isn’t a bad choice.

First thing: What is an R-value? An R-value is an index of how resistant an insulation is to heat movement. This is the opposite of thermal conductivity, which is the ease of heat flow through a material. Generally speaking, a good insulator is going to have a low density and fewer particle-to-particle contact points in the material to conduct heat as heat moves through solid materials by conduction. So light, fluffy materials are best and its even better if air doesn’t move through those materials because heat can be lost via convection as well (think air infiltration, drafts, and air leaks). This is why products like sprayed on closed-cell foam are such effective insulators. They seal gaps, don’t allow air movement, and are low density materials.

How low can the density get? Ever heard of aerogel? It’s an insulator developed by NASA and it is 99+% open space; it’s nicknamed “frozen smoke” and it looks it. It is a phenomenal insulator, but a bit pricey for regular construction; however, it is being manufactured for high-value and small-space applications.

More Insulation Types

Other than spray foams we have various foam board products, different types of batting, and loose insulation made from various new and recycled materials. What is chosen to insulate the roof or attic with depends on expense, availability, and project demands.

If you are in the Midwest, chances are that you are looking for an R-50 or higher value for an attic or roof. This is can be achieved in quite a few different ways. If you are using a really high R-value insulation, such as spray foam (which is a bonus because it seals air leaks too) then you can expect to apply 8”-9” of spray foam to achieve this target. That gets expensive.

Also, it isn’t quite right. Because of the air sealing that comes with spray foam, you don’t actually need to hit this target to reduce heat loss to the necessary amount. There are some pretty serious diminishing returns as thicker foam is applied. Going from 5” of spray foam to 8”, you only reduce heat flow about 2% and at a pretty hefty price tag. Plus you have already sealed any drafts or air leaks with the first 2” or 3”.

Insulation Combos

There is a possibility of simply applying a thin coat of spray foam and then another type of insulation, such as loose fiberglass over the top. This approach would achieve the air sealing from the foam and a less expensive way to achieve the desired R-value.

When I asked Dan Heinen, a contractor in Kansas, about this approach, he said, “Yeah you could do that and I have heard of other people doing it, but most of the time if we have someone spraying the foam, we just go ahead and fill it up to hit the R-value we’re looking for.” So I guess it all depends on the costs associated.

A neighbor of mine used a combo of spray foam and foam board insulation to get the air sealing effect along with the ease of using foam board on a retrofit with good results. In this case he applied the foam board first and then spray foamed to seal up any gaps and cover up any odd shapes and corners.

Loose Insulation

If you are using loose insulation (blown-in insulation) then you need anywhere from 12” to about 20” of insulation in the attic, depending on the product used. The benefit of loose insulation is the ease of installation as you can pretty much blow it in anywhere and easily fill cavities at a lower expense than a spray foam.

But there are downsides. Loose insulation like this settles over time (often unevenly), which can lead to cold spots. My own experience with this showed up in our current home where the loose insulation had settled and was only about 12” thick when I inspected the attic. One could try to fluff that insulation up, but I opted to have a contractor come out and blow in an additional 8” of new material on top. Having settled, the previous insulation was no longer as effective as it had compressed (remember that density thing), which is why I opted to add some new material on top.

An additional issue with loose insulation — and potentially with batts — is rodents. They will tunnel all around in that stuff and make it less effective. Controlling vermin is always in your best interest (I had to put poison out in my attic for this very reason).

Batting

If batts are chosen, then you are looking at about 15” of batting that you would need to install to achieve R-50. Something to consider here with batts is the future. While batts may be more difficult to install than loose insulation or spray foam, they do have an advantage when it comes to any future change, addition, or remodeling the homeowners may do. Batts are easy to take out and move around. When retrofitting an attic to make a loft, loose fill can be a bit of a pain.

[There is nothing like shoveling loose insulation in a 115°F attic let me tell you! And what’s more, when you cut out that first piece of sheet rock from the ceiling and the remnants slide off into your face… but I digress.]

If the homeowner will be making lots of future changes such as lighting or modification of an attic this is something to consider.

Surface Impact on Insulation Choice

Obviously, the choice that you make is contingent on the surface you are insulating. When insulating an attic a common choice is loose insulation due to the lower cost of materials and ease of installation. But if the roof has to be insulated then it’s either batts, foam board or spray foam due to the angle (yes, if you create closed cavities you can blow in loose fill, but you run the risk of a lot of settling). In a renovation project on my own house, I opened up a loft in my attic and needed to insulate the roof as a result. I didn’t have much space to work with so I needed a high R-value product plus it was a slanted surface, so I went with spray foam. In this install we were careful to create a gap between the roof deck and the insulation so that the soffit vents and continuous ridge vent could still function as designed. This was accomplished with 2” x 4” blocking and plywood between the 2” x 12” rafters.

Take Moisture Into Account

A final concern to take into account is moisture. You really don’t want the insulation to get wet as it can cause mold and a reduction in the effectiveness of the insulation. Just like a down-filled coat (an extreme example), insulation will lose its R-value when damp. For this reason air flow and ventilation are important.

You can insulate a roof directly, but it is better to have some ventilation between the roof deck and the insulation. If it is desirable to insulate a roof directly there are some additional benefits. It seals up cracks and air leaks and it can increase the structural integrity of the roof (basically bonding the decking to the rafters), and provide a meaningful reduction in heat loss through the roof.

An additional consideration is a vapor barrier as part of the insulation plan. Remember that this needs to go on the warm side. Being the beneficiary of a high quality insulation job, my home has a continuous vapor barrier. This was achieved on my house with a plastic-type wrap between the sheetrock and studs as well as the trusses. Spray foam creates its own vapor barrier. A vapor barrier like this helps to prevent moisture from the living space moving into the insulation, while the ventilation of an attic or roof helps to prevent condensation on top of the insulation. l

Jacob Prater is a Soil Scientist and Associate Professor in Wisconsin. His passion is natural resource management along with the wise and effective use of those resources to improve human life.