By David A. Rockman and Jessica L. Rosenblatt

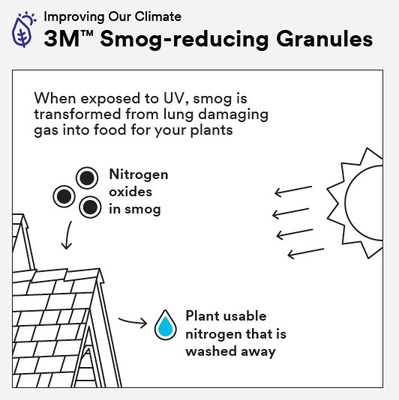

Polyvinyl chloride, better known as PVC or vinyl, is one of the most commonly used plastic polymers in the world. However, following a long-awaited settlement agreement with environmental advocates earlier this year, EPA is now tasked with determining whether PVC should be regulated as a hazardous waste.

On May 4, 2022, EPA published notice of a proposed consent decree that would resolve allegations by the Center for Biological Diversity (CBD) that it unreasonably delayed in acting on a 2014 petition to list discarded PVC as hazardous waste under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act. Under the agreement, EPA must issue a tentative decision on classifying the material as hazardous waste by January 20, 2023, and a final decision by April 12, 2024.

Background

PVC is the most commonly used plastic in the building and construction industry due to its low cost and durability. It is a mainstay in building and construction materials so much so that it is known as the “infrastructure plastic.” Industry estimates indicate that upwards of 70% of all PVC produced is used for building and construction, where it is commonly found in windows, pipes, ductwork, roofing, flooring, and cables. Outside of the building and construction industry, PVC is readily used to make children’s toys, medical devices, clothing, electronics, household goods, consumer packaging, and many other products.

Plastic pvc pipes, isolated on the white

Approximately seven billion pounds of PVC are discarded each year in the United States with experts anticipating those amounts will only increase in the near future. Additionally, PVC makes up a substantial portion of ocean litter, which already consists of as much as eighty percent lightweight and durable plastic trash. A significant portion of discarded PVC products are attributed to the building and construction industry.

Some experts believe PVC may cause health problems, including reproductive harm, abnormal brain development, obesity, liver damage and cancer. CBD has argued for its regulated disposal for nearly a decade, asserting that it is toxic to human health, wildlife, and the environment, particularly after its disposal when CBD further asserts that harmful components may leach out of PVC and contaminate the surrounding environment.

CBD’s petition not only asks that PVC be regulated as a hazardous waste at the initial chemical manufacturing stage but also at the stage of finished materials and products. This could have significant consequences for industries like building and construction that utilize and discard large amounts of PVC on a regular basis. If EPA proceeds with listing PVC as a hazardous waste, it will be tasked with developing a comprehensive framework for regulating its safe use, storage and disposal. Common materials, such as discarded PVC drill cuttings and leftover PVC pipe and flooring, would likely be regulated as hazardous waste.

Defining Hazardous Waste

Regulation of discarded PVC materials as hazardous waste would impose a host of regulatory requirements across a broad spectrum of businesses and activities. Initially, it is important to note that a material is not a hazardous waste until it is first a “waste.” Under federal law, a material is only a waste once discarded or abandoned, although the regulatory structure becomes more complex for materials that are recycled or reused in some manner.

Because hazardous waste regulations are only triggered once a material becomes a waste, PVC materials that are in inventory and/or being used are not subject to hazardous waste regulations. Those actually used or installed in a project are similarly free from regulation. However, PVC materials that are left over from a project and not subject to being reused or used elsewhere, such as cut-off scraps and damaged pieces, would be considered waste, and therefore could potentially be considered hazardous waste if EPA elects to regulate PVC.

Importantly, while excess PVC materials not used on a project can be collected and stored pending future use without being considered waste, these materials would have to have a legitimate potential future use. They cannot simply be stored indefinitely under the guise of being stored for future use if there is no realistic chance that they will be used within a reasonable time frame.

Typically, a hazardous waste evaluation begins once a material is considered waste. At that point, the party that is generating the waste (in a construction project, most typically the party that is using the PVC material) needs to determine if it is hazardous. Whether a waste is hazardous depends on how it is classified in the relevant regulations.

There are two basic types of hazardous waste: listed hazardous waste and characteristic hazardous waste. Listed hazardous wastes are materials that are specifically identified in the regulations as being hazardous. They are described in terms of the type of substance and/or the process that generated the substance. Characteristic hazardous wastes are designated based on four categories – toxicity, reactivity, ignitability and corrosivity – pursuant to specifications listed in the regulations.

Looking Ahead

It is expected that any designation of PVC materials as hazardous waste would be done by creating a new category of listed hazardous waste specifically for PVC materials. This would allow for distinctions to be introduced between certain types of PVC materials and/or based on the project or process that resulted in the generation of the PVC waste.

It is unlikely that hazardous waste classification for waste PVC materials would be based on volume or amount of PVC waste, or at least not solely based on volume or amount, since this is a factor that could potentially be easily manipulated to avoid the application of the regulations. The hazardous waste program does contain distinctions related to the amount of waste created, but those apply on a generator level – for example, the amount of hazardous waste that a company produced within a month or a year. These volume-based distinctions apply to all hazardous waste created by a company and affect aspects of the hazardous waste program such as storage of waste and reporting obligations. They do not affect other substantive requirements such as proper handling and disposal of hazardous waste.

Hazardous Waste Requirements

Broadly speaking, the basic elements of hazardous waste regulations govern how hazardous waste materials are handled and disposed. Employees that handle hazardous waste are required to be trained, and facilities where hazardous waste is generated or stored are subject to contingency planning requirements. Hazardous wastes can only be stored in designated storage areas, are subject to labelling requirements, and can only remain in storage for set periods of time before they have to be disposed (the length of time depends on how much hazardous waste is created by the generator). Hazardous waste manifests are required for the shipment of hazardous wastes.

Hazardous waste requirements are imposed at both the state and federal level, although the requirements tend to be nearly identical. The federal requirements, administered by the US Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA), set the minimum requirements, and individual states can regulate more stringently if they so choose. In practice, most states adopt or incorporate the federal hazardous waste program with essentially no changes. Both US EPA and the state environmental agency can enforce these hazardous waste requirements.

Challenges Associated with PVC

The potential regulation of PVC waste as hazardous waste presents unique issues because of the pervasive use of PVC in building materials. Such regulation would be unique in that it would affect a vast number of companies, projects and activities that do not otherwise trigger hazardous waste regulations. Many of the affected parties will not have familiarity with the hazardous waste program or the nuances necessary to achieve and maintain compliance. Further, such regulations will impact job sites where the property in question is not owned by the contractor generating the PVC waste and where such contractor may have limited control over activities on, and access to, the property. This scenario introduces significant complexities as compared to the generation of hazardous waste at a traditional manufacturing facility.

Hazardous waste regulation of PVC materials will increase both cost and risk associated with construction and demolition projects. Cost will increase arising out of on-site management responsibilities as well as from increased costs for disposal of waste PVC materials. There will also be liability risk associated with the disposal of PVC materials, if done improperly. Insuring against environmental liability risks tends to be complex at best, and frequently cost-prohibitive.

Public Comment

The public will have the opportunity to comment on US EPA’s decision whether or not to regulate PVC waste as hazardous waste, and also to comment on any rule proposed by US EPA to accomplish such regulation of PVC waste materials. l

David Rockman is a member in Eckert Seamans Pittsburgh office and chair of the firm’s environmental practice group. Mr. Rockman helps clients manage environmental compliance and environmental risks and assists them with understanding and meeting their legal obligations with respect to federal, state, and local environmental laws, regulations, and permits.

Jessica Rosenblatt is an associate attorney at Eckert Seamans Pittsburgh office, helping clients address the challenges arising under federal and state environmental laws. She advises on compliance issues, navigates permitting processes, manages environmental risks in transactions, and helps resolve environmental disputes and enforcement actions.